Physicists Decode the Cosmic Dance of Auroras on Earth, Jupiter, and Saturn

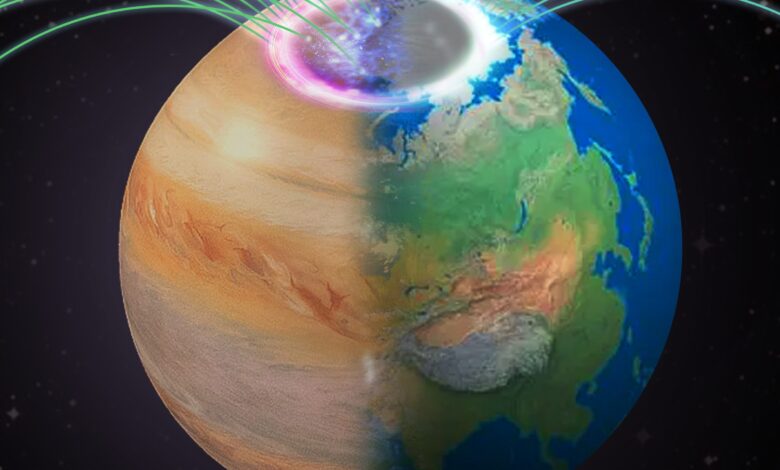

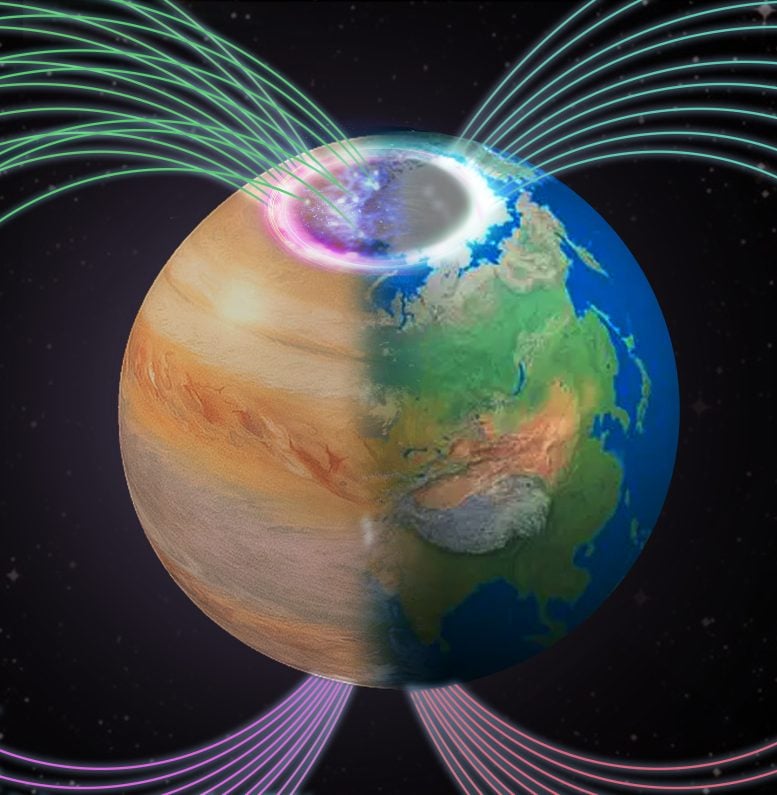

A conceptual image illustrating the different aurora between Earth and Jupiter. Credit: Professor Zhonghua Yao, The University of Hong Kong

A recent study reveals new insights into aurorae across Earth, Jupiter, and Saturn, highlighting the role of magnetic fields and solar winds in shaping these phenomena, with significant implications for space weather forecasting and planetary exploration.

The breathtaking aurorae, commonly known as the Northern and Southern Lights, have captivated human imagination for centuries. From May 10th to 12th, 2024, the most powerful aurora event in 21 years showcased the extraordinary beauty of these celestial light displays.

Recently, space physicists from the Department of Earth Sciences at The University of Hong Kong (HKU), including Professor Binzheng Zhang, Professor Zhonghua Yao, and Dr Junjie Chen, along with their international collaborators, have published a paper in Nature Astronomy that explores the fundamental laws governing the diverse aurorae observed across planets, such as Earth, Jupiter and Saturn. This work provides new insights into the interactions between planetary magnetic fields and solar wind, updating the textbook picture of giant planetary magnetospheres. Their findings can improve space weather forecasting, guide future planetary exploration, and inspire further comparative studies of magnetospheric environments.

Unraveling the diversity of planetary aurorae

Earth, Saturn, and Jupiter all generate their own dipole-like magnetic field, resulting in funnel-canopy-shaped magnetic geometry that leads the space’s energetic electrons to precipitate into polar regions and cause polar auroral emissions. On the other hand, the three planets differ in many aspects, including their magnetic strength, rotating speed, solar wind condition, moon activities, etc. It is unclear how these different conditions are related to the different auroral structures that have been observed on those planets for decades.

Using three-dimensional magnetohydrodynamics calculations, which model the coupled dynamics of electrically conducting fluids and electromagnetic fields, the research team assessed the relative importance of these conditions in controlling the main auroral morphology of a planet. Combining solar wind conditions and planetary rotation, they defined a new parameter that controls the main auroral structure, which for the first time, nicely explains the different auroral structures observed at Earth, Saturn, and Jupiter.

Stellar winds’ interaction with planetary magnetic fields is a fundamental process in the universe. The research can be applied to grasp the space environments of Uranus, Neptune, and even exoplanets.

‘Our study has revealed the complex interplay between solar wind and planetary rotation, providing a deeper understanding of aurorae across different planets. These findings will not only enhance our knowledge of the aurorae in our solar system but also potentially extend to the study of aurorae in exoplanetary systems,’ said Professor Binzheng Zhang, Principal Investigator and the first author of the project.

‘We have learnt that the aurorae at Earth and Jupiter are different since 1979, it is a big surprise that they can be explained by a unified framework,’ added Professor Denis GRODENT, Head of the STAR institute at the University of Liege and co-author of the project.

By advancing our fundamental understanding of how planetary magnetic fields interact with the solar wind to drive auroral displays, this research has important practical applications for monitoring, predicting, and exploring the magnetic environments of the solar system.

This study also represents a significant milestone in understanding auroral patterns across planets that deepened our knowledge of diverse planetary space environments, paving the way for future research into the mesmerizing celestial light shows that continue to capture our imagination.

Reference: “A unified framework for global auroral morphologies of different planets” by B. Zhang, Z. Yao, O. J. Brambles, P. A. Delamere, W. Lotko, D. Grodent, B. Bonfond, J. Chen, K. A. Sorathia, V. G. Merkin and J. G. Lyon, 20 May 2024, Nature Astronomy.

DOI: 10.1038/s41550-024-02270-3