Over a Hundred Times Smaller Than the Width of a Hair – Revolutionary Tiny Sensor Reveals Hidden Neuron Activity

Rice University researchers have developed a new implantable sensor, spinalNET, capable of recording the electrical activity of spinal neurons in freely moving subjects. This breakthrough could help unlock the complexities of how spinal neurons process sensory and motor functions, potentially leading to better treatments for spinal cord diseases and injuries.

Implantable technologies have significantly improved our ability to study and even modulate the activity of neurons in the brain. However, neurons in the spinal cord are harder to study in action.

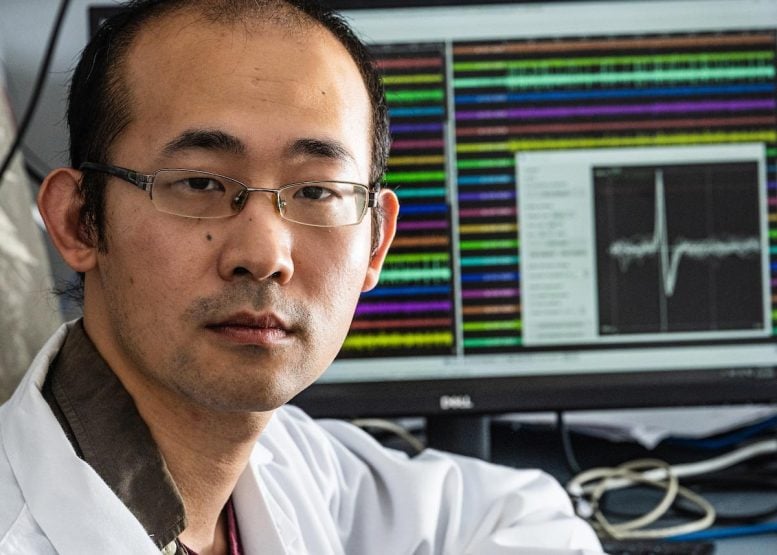

“If we understood exactly how neurons in the spinal cord process sensation and control movement, we could develop better treatments for spinal cord disease and injury,” said Yu Wu, a research scientist who is part of a team of Rice University neuroengineers working on a solution to this problem.

Introducing spinalNET: A Breakthrough in Neuronal Monitoring

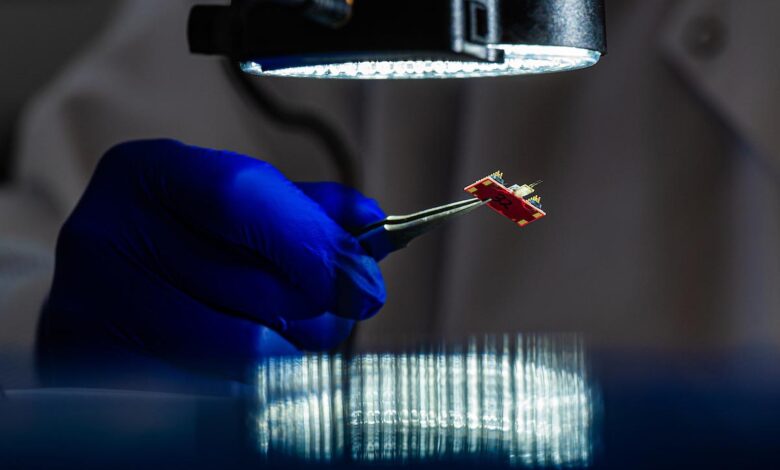

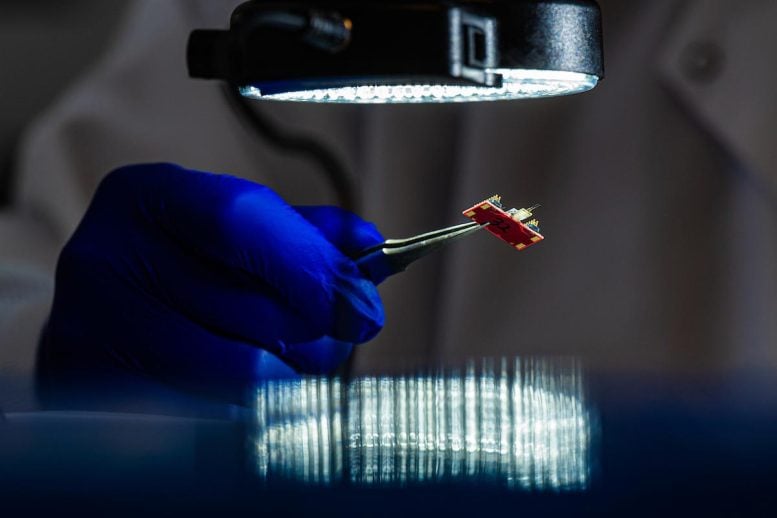

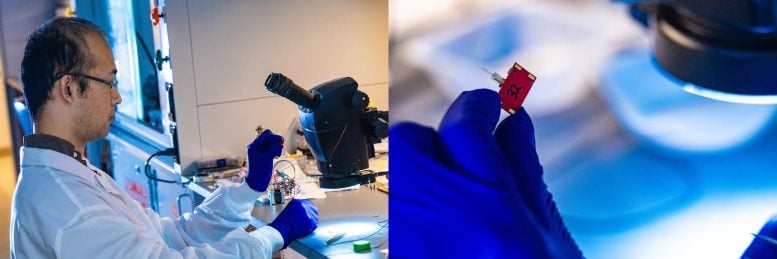

“We developed a tiny sensor, spinalNET, that records the electrical activity of spinal neurons as the subject performs normal activity without any restraint,” said Wu, who is the lead author of a study about the sensor published in Cell Reports. “Being able to extract such knowledge is a first but important step to develop cures for millions of people suffering from spinal cord diseases.”

According to the study, the sensor recorded neuronal activity in the spinal cord of freely moving mice for prolonged periods and with great resolution, even tracking the same neuron over multiple days.

Challenges in Spinal Cord Monitoring

“Up until now, the spinal cord has been more or less a black box,” said Lan Luan, an associate professor of electrical and computer engineering and a corresponding author on the study. “The issue is that the spinal cord moves so much during normal activity. Every time you turn your head or bend over, spinal neurons are also moving.”

During such movements, rigid sensors implanted in the spinal cord inevitably disturb or even damage the fragile tissue. SpinalNET, however, is over a hundred times smaller than the width of a hair, which makes it extremely soft and flexible ⎯ nearly as soft as the neural tissue itself.

“This flexibility gives it the stability and biocompatibility we need to safely record spinal neurons during spinal cord movements,” said Chong Xie, an associate professor of electrical and computer engineering and bioengineering and a corresponding author of the study. “With spinalNET, we were able to get low-noise signals from hundreds of neurons.”

Insights and Future Directions in Spinal Research

The spinal cord plays a critical role in controlling movement and other vital functions, and the ability to record spinal neurons with fine-grained spatial and temporal resolution during unrestrained motion offers a window into the mechanisms that make this possible. Using spinalNET, researchers discovered that the spinal neurons in the central pattern generator — the neuronal circuit that can produce rhythmic motor patterns such as walking in the absence of specific timing information — seem to be involved with a lot more than rhythmic movement.

“Some of them are strongly correlated with leg movement, but surprisingly, a lot of neurons have no obvious correlation with movement,” Wu said. “This indicates that the spinal circuit controlling rhythmic movement is more complicated than we thought.”

The researchers said they hope to help unravel some of this complexity in future research, tackling questions such as the difference between how spinal neurons process reflex motion ⎯ getting startled, for instance ⎯ versus volitional action.

“In addition to scientific insight, we believe that as the technology evolves, it has great potential as a medical device for people with spinal cord neurological disorders and injury,” Luan said.

Reference: “Ultraflexible electrodes for recording neural activity in the mouse spinal cord during motor behavior” by Yu Wu, Benjamin A. Temple, Nicole Sevilla, Jiaao Zhang, Hanlin Zhu, Pavlo Zolotavin, Yifu Jin, Daniela Duarte, Elischa Sanders, Eiman Azim, Axel Nimmerjahn, Samuel L. Pfaff, Lan Luan and Chong Xie, 9 May 2024, Cell Reports.

DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2024.114199

Funding: The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01NS102917, U01NS115588, U01NS131086, R01NS109361, R01NS123160, R01NS108034, U19NS112959), Rice, the Salk Institute, and the Mary K. Chapman Foundation.

Source link