Jupiter’s Twin? Webb Telescope Unveils a Frosty Look-Alike Just 12 Light-Years Away

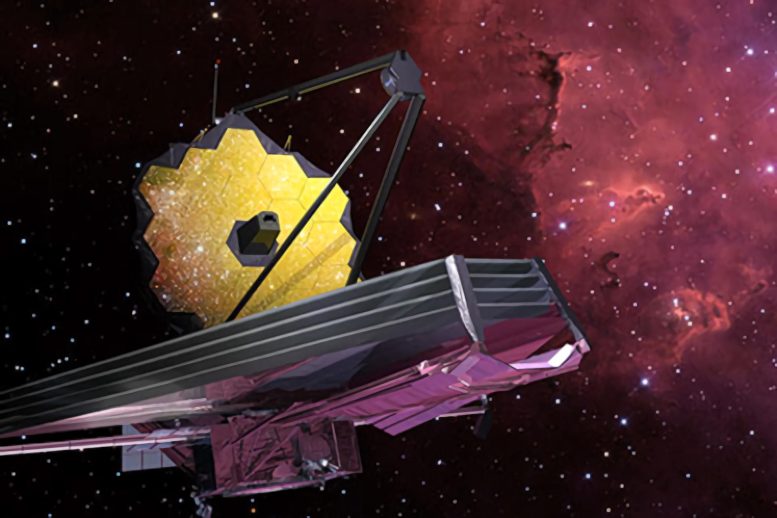

The James Webb Space Telescope has directly imaged Epsilon Indi Ab, a cold, Jupiter-like exoplanet 12 light-years away. This discovery is crucial as it provides insights into the atmospheric properties of a planet colder than most known exoplanets and helps refine our understanding of planetary systems beyond our own. (Artist’s concept.) Credit: SciTechDaily.com

Epsilon Indi Ab is colder than any other imaged planet beyond our solar system.

If alien astronomers in a nearby star system had a telescope like NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, and they pointed it toward our solar system, then Jupiter might look very much like this new Webb image of the exoplanet Epsilon Indi Ab. It is one of the coldest exoplanets to be directly detected, with an estimated temperature of 35 degrees Fahrenheit (2 degrees Celsius). Epsilon Indi Ab is only around 180 degrees Fahrenheit (100 degrees Celsius) warmer than gas giants in our solar system. With so many known exoplanets looking nothing like the planets in our solar system, Epsilon Indi Ab provides a rare opportunity for astronomers to study the atmospheric composition of true solar system analogs.

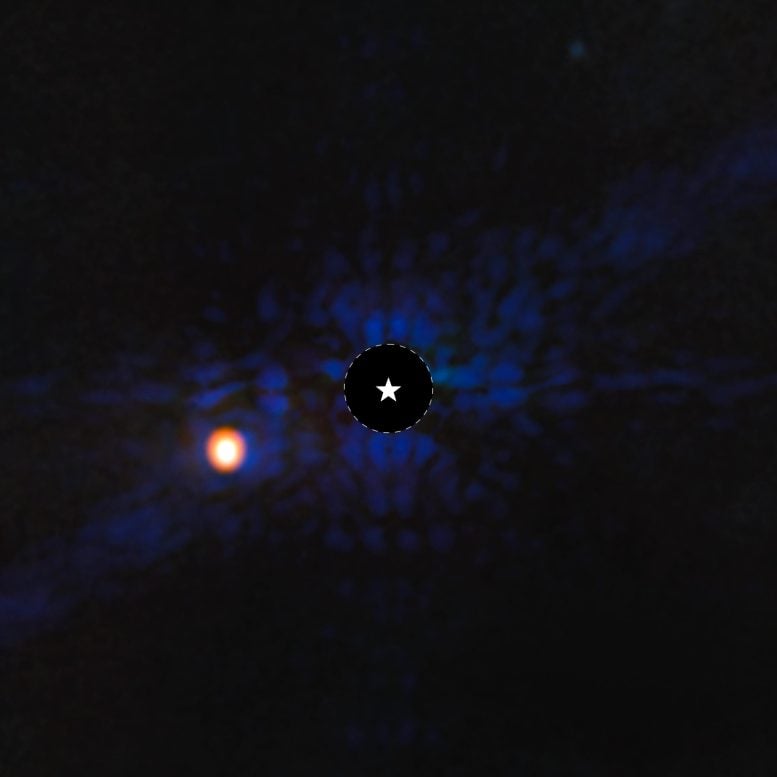

This image of the gas-giant exoplanet Epsilon Indi Ab was taken with the coronagraph on NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope’s MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument). A star symbol marks the location of the host star Epsilon Indi A, whose light has been blocked by the coronagraph, resulting in the dark circle marked with a dashed white line. Epsilon Indi Ab is one of the coldest exoplanets ever directly imaged. Light at 10.6 microns was assigned the color blue, while light at 15.5 microns was assigned the color orange. MIRI did not resolve the planet, which is a point source. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Elisabeth Matthews (MPIA)

Webb Space Telescope Images Cold Exoplanet 12 Light-Years Away

An international team of astronomers using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope has directly imaged an exoplanet roughly 12 light-years from Earth. The planet, Epsilon Indi Ab, is one of the coldest exoplanets observed to date.

The planet is several times the mass of Jupiter and orbits the K-type star Epsilon Indi A (Eps Ind A), which is around the age of our Sun, but slightly cooler. The team observed Epsilon Indi Ab using the coronagraph on Webb’s MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument). Only a few tens of exoplanets have been directly imaged previously by space- and ground-based observatories.

“Our prior observations of this system have been more indirect measurements of the star, which actually allowed us to see ahead of time that there was likely a giant planet in this system tugging on the star,” said team member Caroline Morley of the University of Texas at Austin. “That’s why our team chose this system to observe first with Webb.”

“This discovery is exciting because the planet is quite similar to Jupiter — it is a little warmer and is more massive, but is more similar to Jupiter than any other planet that has been imaged so far,” added lead author Elisabeth Matthews of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Germany.

Since its 2021 launch, the James Webb Space Telescope has been peering into the universe’s earliest moments with its advanced infrared capabilities and large mirror. It provides detailed insights into galaxies, stars, and exoplanets, significantly enhancing our cosmic understanding. Credit: NASA

A Solar System Analog

Previously imaged exoplanets tend to be the youngest, hottest exoplanets that are still radiating much of the energy from when they first formed. As planets cool and contract over their lifetime, they become significantly fainter and therefore harder to image.

“Cold planets are very faint, and most of their emission is in the mid-infrared,” explained Matthews. “Webb is ideally suited to conduct mid-infrared imaging, which is extremely hard to do from the ground. We also needed good spatial resolution to separate the planet and the star in our images, and the large Webb mirror is extremely helpful in this aspect.”

Epsilon Indi Ab is one of the coldest exoplanets to be directly detected, with an estimated temperature of 35 degrees Fahrenheit (2 degrees Celsius) — colder than any other imaged planet beyond our solar system, and colder than all but one free-floating brown dwarf. The planet is only around 180 degrees Fahrenheit (100 degrees Celsius) warmer than gas giants in our solar system. This provides a rare opportunity for astronomers to study the atmospheric composition of true solar system analogs.

“Astronomers have been imagining planets in this system for decades; fictional planets orbiting Epsilon Indi have been the sites of Star Trek episodes, novels, and video games like Halo,” added Morley. “It’s exciting to actually see a planet there ourselves, and begin to measure its properties.”

Not Quite As Predicted

Epsilon Indi Ab is the twelfth closest exoplanet to Earth known to date and the closest planet more massive than Jupiter. The science team chose to study Eps Ind A because the system showed hints of a possible planetary body using a technique called radial velocity, which measures the back-and-forth wobbles of the host star along our line of sight.

“While we expected to image a planet in this system, because there were radial velocity indications of its presence, the planet we found isn’t what we had predicted,” shared Matthews. “It’s about twice as massive, a little farther from its star, and has a different orbit than we expected. The cause of this discrepancy remains an open question. The atmosphere of the planet also appears to be a little different than the model predictions. So far we only have a few photometric measurements of the atmosphere, meaning that it is hard to draw conclusions, but the planet is fainter than expected at shorter wavelengths.”

The team believes this may mean there is significant methane, carbon monoxide, and carbon dioxide in the planet’s atmosphere that are absorbing the shorter wavelengths of light. It might also suggest a very cloudy atmosphere.

The direct imaging of exoplanets is particularly valuable for characterization. Scientists can directly collect light from the observed planet and compare its brightness at different wavelengths. So far, the science team has only detected Epsilon Indi Ab at a few wavelengths, but they hope to revisit the planet with Webb to conduct both photometric and spectroscopic observations in the future. They also hope to detect other similar planets with Webb to find possible trends about their atmospheres and how these objects form.

NASA’s upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope will use a coronagraph to demonstrate direct imaging technology by photographing Jupiter-like worlds orbiting Sun-like stars – something that has never been done before. These results will pave the way for future missions to study worlds that are even more Earth-like.

These results were taken with Webb’s Cycle 1 General Observer program 2243 and have been published in the journal Nature.

For more on this discovery, see JWST’s Super-Jupiter Breakthrough: Oldest and Coldest Exoplanet Ever Imaged.

Reference: “A temperate super-Jupiter imaged with JWST in the mid-infrared” by E. C. Matthews, A. L. Carter, P. Pathak, C. V. Morley, M. W. Phillips, S. Krishanth P. M, F. Feng, M. J. Bonse, L. A. Boogaard, J. A. Burt, I. J. M. Crossfield, E. S. Douglas, Th. Henning, J. Hom, C.-L. Ko, M. Kasper, A.-M. Lagrange, D. Petit dit de la Roche and F. Philipot, 24 July 2024, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-07837-8

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), launched on December 25, 2021, represents a monumental leap forward in astronomical capabilities. As the successor to the Hubble Space Telescope, JWST is designed to observe the universe primarily in the infrared spectrum, allowing it to peer through cosmic dust and gaze at the universe’s earliest moments. Its large, segmented primary mirror, spanning 6.5 meters, and advanced suite of scientific instruments enable the telescope to capture extraordinarily detailed images of distant galaxies, star-forming nebulae, and exoplanets, providing unprecedented insights into the origins of stars, planetary systems, and the universe itself. The JWST is a collaborative endeavor involving NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA), and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), and is expected to fundamentally transform our understanding of the cosmos.