Discover How Ancient Europeans Survived the Ice Age With Just Their Teeth

A large-scale study of fossil human teeth from Ice Age Europe shows that climate change significantly influenced the demography of prehistoric humans.

New research based on extensive human fossil records from Ice Age Europe shows how ancient populations dealt with dramatic climate shifts. By analyzing dental data with a machine learning algorithm, the study details migration trends, population dynamics, and the significant effects of the Last Glacial Maximum.

Using the largest dataset of human fossils from Ice Age Europe to date, an international research team shows how prehistoric hunter-gatherers coped with climate change in the period between 47,000 and 7,000 years ago. Population sizes declined sharply during the coldest period, and in the West, Ice Age Europeans even faced extinction, according to the study published on August 16 in the journal Science Advances.

Lead investigator Dr. Hannes Rathmann from the Senckenberg Centre for Human Evolution and Palaeoenvironment at the University of Tübingen (Germany) developed a new method for analyzing the fossils based on a machine learning algorithm, in collaboration with colleagues from the University of Tübingen, University of Ferrara (Italy) and New York University (USA).

Advancements in Archaeological Methods

Around 45,000 years ago, the first modern humans migrated to Europe during the last Ice Age, marking the beginning of the so-called “Upper Paleolithic.” These early groups continuously populated the European continent – even during the so-called “Last Glacial Maximum” about 25,000 years ago, when glaciers covered large parts of northern and central Europe.

“Archaeologists have long debated the influence of climatic changes and the associated new environmental conditions on the demography of hunter-gatherers at that time. Due to the limited number of fossils available and their often poor molecular preservation for ancient DNA analysis, it has been very difficult to draw conclusions about the impact of climatic factors on migration, population growth, decline, and extinction,” explains the study’s first author, Dr. Hannes Rathmann from the Senckenberg Centre for Human Evolution and Palaeoenvironment at the University of Tübingen.

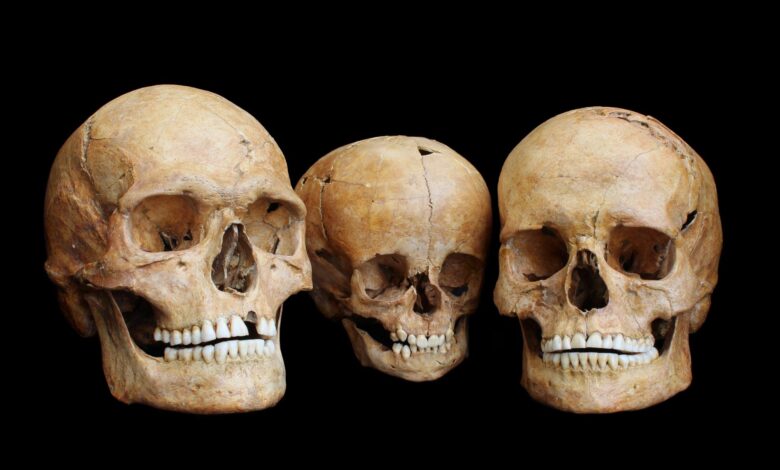

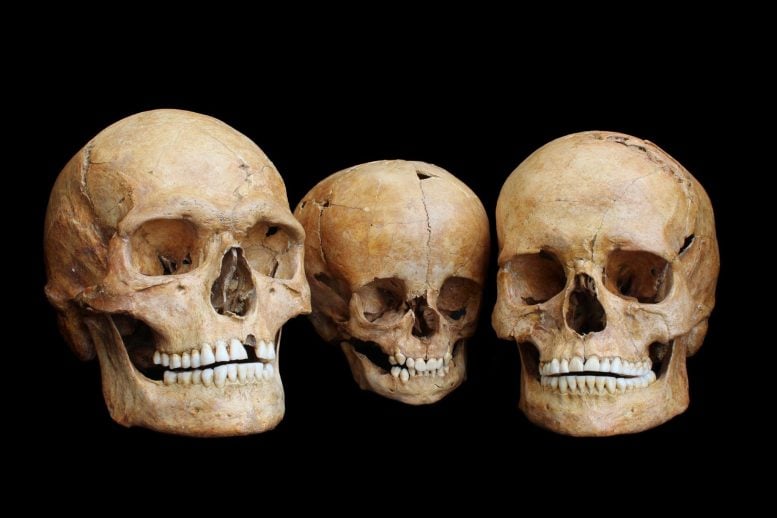

Together with a research team from Italy, the USA, and Germany, Rathmann therefore chose a new approach to clarify this question: Instead of analyzing the few scattered prehistoric individuals for which ancient DNA is available, the team examined their teeth. “Teeth are the hardest tissue in the human body and are therefore the most common fossil skeletal elements found by archaeologists.

Innovative Data Collection Techniques

This has allowed us to collect an unprecedented dataset that is significantly larger than previous skeletal and genetic datasets. Our newly compiled collection includes dental data of 450 prehistoric humans from all over Europe, covering the period between 47,000 and 7,000 years ago,” explains Rathmann.

The researchers focused on “morphological” tooth traits – small variations within the dentition, such as the number and shape of crown cusps, ridge and groove patterns on the chewing surface, or the presence or absence of wisdom teeth.

“These traits are heritable, which means we can use them to trace genetic relationships among Ice Age humans without requiring well-preserved ancient DNA,” explains Rathmann. As these features can be observed with the naked eye, the team also examined hundreds of published photographs of fossils. “Examining historical photographs for dental traits was particularly exciting, as it allowed us to include important fossils that unfortunately no longer exist, such as those lost or destroyed during World War II,” says Rathmann.

The study’s results show that from around 47,000 to 28,000 years ago – during the “Middle Pleniglacial” – populations in Western and Eastern Europe were genetically well connected. “This finding is consistent with our previous knowledge from archaeological studies, which identified widespread similarities in stone tools, hunting weapons, and portable art from the different regions,” explains co-author Dr. Judith Beier from the DFG Center for Advanced Studies “Words, Bones, Genes, Tools” at the University of Tübingen.

During this period, Europe was largely characterized by open steppe landscapes that could support large herds of mammals – the main source of food for hunter-gatherers. These conditions likely favored the interlinking of populations.

Genetic Disconnections and Climatic Challenges

In the subsequent period, the “Late Pleniglacial” between 28,000 and 14,700 years ago, the researchers found no genetic connections between Western and Eastern Europe. In addition, the analyses show that both regions experienced a significant reduction in population size, which led to a loss of genetic diversity.

“This drastic demographic change was probably caused by massive climate changes: Temperatures during this period dropped to the lowest values of the entire Upper Paleolithic and culminated in the Last Glacial Maximum, a time when ice sheets reached their greatest extent and covered most of northern and central Europe,” explains the scientist from Tübingen. “The deteriorating climate caused a shift in vegetation from steppe to a predominantly tundra landscape, which affected the habitats of prey animals and, consequently, the hunter-gatherers who depended on them,” explains Rathmann.

“Our results support the long-held theory that populations were not only driven southward by advancing ice sheets but also separated into largely isolated refugia with more favorable environmental conditions,” adds Beier. Another remarkable finding of the study is the discovery that populations in Western Europe went extinct at the transition from the Middle to the Late Pleniglacial and were replaced by a new population that migrated from Eastern Europe.

Resurgence and Recovery of Populations

After the Late Pleniglacial, temperatures steadily rose again, glaciers retreated, and steppe and forest vegetation returned, allowing for the first recolonization of previously abandoned areas. The research team observed that during this period, the previously isolated and greatly reduced populations in Western and Eastern Europe began to grow again in numbers and migration between the regions resumed.

“Our new method – which is based on a machine learning algorithm we call Pheno-ABC – has enabled us for the first time to reconstruct complex prehistoric demographic events using morphological data. As far as we know, this has never been achieved before,” says the co-first author Dr. Maria Teresa Vizzari from the University of Ferrara, who played a key role in developing the algorithm.

The new analytical tool makes it possible to identify the most likely demographic scenario among many that were tested. According to the researchers, the Pheno-ABC method could revolutionize the analysis of fossil skeletal morphology in the future.

Conclusion: Learning From the Past

“Our study provides important insights into the demographic history of Ice Age Europeans and highlights the profound impact of climate and environmental changes on the lives of prehistoric humans. We should urgently learn from our past if we want to address the complex environmental problems of the future,” adds Rathmann in conclusion.

Reference: “Human population dynamics in Upper Paleolithic Europe inferred from fossil dental phenotypes” by Hannes Rathmann, Maria T. Vizzari, Judith Beier, Shara E. Bailey, Silvia Ghirotto and Katerina Harvati, 16 August 2024, Science Advances.

DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adn8129

Source link